Home Delivery of Education and Culture

Publisert den 17. jun 2020

Latin America was the last world region hit by the coronavirus pandemic. However, the effects were no different from those in other regions and, as of June 2020, the World Health Organization had declared it the new “red zone” of Covid-19. Like everywhere else, the new virus brought about changes for which not all of us were ready.

After the coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, Mexico became the first country to implement the proceedings and guidelines of the International Sanitary Regulations to deal with the pandemic. When the first case of contagion in the country was confirmed, president Andrés Manuel López Obrador asked Dr. Hugo López-Gatell, deputy secretary of Health and an expert in Epidemiology, to inform the public on the pandemic through daily press conferences. His constant appearances and Quédate en casa (Stay at home) calls eventually made him win hordes of followers, especially women, who openly showed their admiration.

So, while the government started taking measures to deal with the situation, the truth is that most people were rather oblivious. The confinement in China was regarded as something distant and the virus gave way to numerous jokes and memes: piñatas were made, children were dressed as the virus during fiestas, and the Coronavirus Cumbia became a significant hit on Spotify. Not even the spread of the disease in European countries set alarm bells ringing among the majority of the population.

Then, like everywhere else, things changed in a matter of days. If the discussions revolved around women’s rights at the beginning of the second week of March, the government announced the implementation of a general lockdown by the end of that same week. How did the perception change so quickly? During that week, the Mexican media informed that a state of emergency and a nationwide lockdown had been decreed in Spain. In many ways, the mother country is still a reference for many in Latin America, and this news triggered fears that the pandemic was much closer than had been perceived. In this respect, the language was a key factor; for the first time since the outbreak, we were able to hear people sharing horror stories in our language. The shock was immediate. Pressed by society and the media, a lockdown was programmed to start on March 23, only nine days after the one in Spain, where the situation had already spiraled out of control.

In the case of our field, higher education and the announcement of the lockdown meant last-minute changes to our teaching practice to implement distance learning. In this respect, our experience is a sample of Mexican reality in many areas. On the one hand, Juan David was teaching at the National Institute of Public Health, a school equipped with modern technology for online teaching and whose graduate students have access to computers and the internet at home. On the other hand, Victor teaches at the University of Veracruz (UV) where distance learning was possible through the university’s own platform, Eminus, and the support of other resources such as Zoom, Google Classroom, Facebook, WhatsApp, and email. However, in a few cases, students could not continue with their courses: access for students living in rural areas was limited, others did not have the internet at home, and some did not even have a computer.

A similar divide can be found in comparing public and private compulsory level education schools. Children attending private schools represent around 14% of the whole student population, and they usually belong to high-income families who are much interested in quality education. On the other hand, the number of students attending public schools is more varied and can include both higher and lower-income families whose access to technology is not guaranteed. According to the National Institute of Geography and Statistics (INEGI), in 2018, only two-thirds of the population in Mexico over the age of 6 (65.8%) have access to the internet. Differences are also significant between urban and rural communities: while 73.1% of the former have access to the internet, only 40.6% of the latter do. On average, only 55% of school-age children have a computer at home. In either case, the school system in Mexico was not prepared for such a sudden change, and the situation was difficult at times, even chaotic

As opposed to universities, compulsory level schools did not have an online platform they could use, and for a great deal of teachers the most urgent matter was to provide education by any means. Some decided to use Google Classroom, but since access to the internet was limited, WhatsApp became the preferred means of communication. This was not always the best solution. Welcome at the beginning as an emergency solution, this sometimes led to stressful situations. Instructions were at times misunderstood by parents, who then called teachers at any time of the day. In other instances, parents complained homework was too hard (or too much). Calling teachers directly became necessary (at teachers’ expense) to work out all problems and misunderstandings.

However, not everything was negative and there were efforts on several fronts to make the confinement more bearable. This was the case of the book industry. Parallel to the calls by the Secretary of Health, the largest public book publisher (Fondo de Cultura Económica, FCE) launched a campaign called Quédate en tu casa leyendo (Stay at home and read). The actions were varied: free downloading of texts about different topics and books for all ages was allowed, an exclusive partnership with other publishers was set to offer discounts for online shopping, both TV and radio shows designed to promote reading were started, cartoonists and authors shared videos where they spoke about their work as well as their own personal experience during the confinement, and book packages were given to health care workers as gifts.

Another essential feature of this campaign was presented on the FCE’s YouTube channel, where poetry reading, and literary debates were broadcasted live. This initiative gained relevance when officers from the Secretary of Health were invited to participate in a poetry reading. Dr. López-Gatell read Spanish poet Miguel Hernández’s Hambre (Hunger) and Ana Lucía de la Garza, director of epidemiology research who also stirred admiration, read Zel Cabrera’s Curandera (Healer). The objective was two-fold: on the one hand, their appearance reinforced the stay-at-home campaign, and on the other, there was a great push to promote reading as a confinement activity.

In our case, Xalapa, our hometown, has long been recognized as a cultural hub, which attracts visitors and students to the many events in large part organized by the UV. The old saying “the show must go on” became more accurate than ever when, in the face of the pandemic, its Direction of Cultural Events decided that artists would perform not on stage but on the internet through a program called Arte desde el interior (Art from within). Thanks to this initiative, concerts, plays, artistic performances, and festivals were conducted and collected more than 600,000 views from 32 countries for two months. It was fortunate that most of these events were free of cost anyway, so financial losses were basically none. Apart from this, the university’s crown jewel, Xalapa’s Symphonic Orchestra (OSX), the oldest in the country, broadcasted past concerts on YouTube. It also launched a program called Conoce a tus musicOSX (Get to know your musicOSX) in which members of the orchestra were interviewed.

The university was not the only entity offering cultural events. Flavia Galeria, an art gallery and restaurant, released a series of videos and live interviews on Facebook in which its employers provided business ideas to other owners of cultural venues on how to better deal with the lockdown. Cinetix, a regional movie theater chain, projected films on special screens or big walls around the city so that families were able to enjoy a movie for the first time in weeks and, in some cases, ever. Finally, in order to please all tastes, a popular radio station, El Patrón, organized “roof concerts” in low-income neighborhoods across the city, playing salsa or other types of regional Mexican music.

The state and city governments are also keen on culture. Aware of the need for financial support, the Veracruz Institute of Culture released a call for artists to apply for funding in order to ensure people’s free access to quality artistic productions. In a joint effort with other cities in Mexico, the city of Xalapa organized a collaboration network called Cultura Adentro (Culture within), promoting artistic and cultural events of all sorts through Facebook and YouTube.

Without any doubt, the pandemic has led to disruption in everybody’s lives in varying degrees. We can consider ourselves lucky that all these changes have only meant a new adaptation to our personal and professional lives. For others, change has translated into uncertainty. If there’s something that we have learned out of all this experience, it is that whatever our trail in life, the best way to cope with the unexpected is resilience.

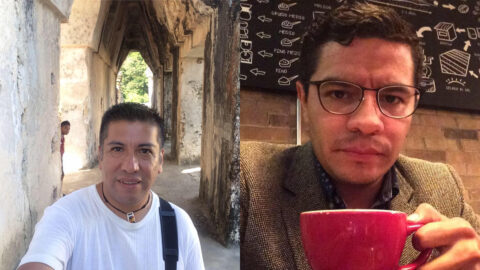

Authors:

Victor Hugo Ramírez Ramírez lives in Xalapa, Mexico. He holds a BA in Languages and International Relations and a Master’s degree in Education. He’s a full-time professor of English at the University of Veracruz. He likes traveling, board games, and small house furniture design.

Juan David Uscanga Castillo lives in Cuernavaca, Mexico. He earned a BSc in Economics and a Master’s degree in Health Economics. He works as Head of the Department of Teaching & Research in a private hospital. He loves drinking coffee, jogging, traveling, and discovering Scandinavian writers.